Next: 4. Experimental Methods Up: Fabrication and characterization of Previous: 2. Device Physics / Contents

|

Goldschmidt was the first who created GaAs in 1929. He found that it has a zincblende lattice with a FCC symmetry [Gol29]. Only in 1952, in fact, GaAs has been identified as a semiconductor by Welker (Siemens)3.1. The nature of the bond between gallium and arsine is predominantly covalent. The first device exploiting the direct band-gap of GaAs dates from 1962, when Hall et al. at GE [HFKC62] and Redhiker at al. at MIT Lincoln Laboratory [QRK+62], independently, obtained the first semiconductor laser. In the same year, Gunn (IBM) discovered the transferred electron effect and developed the first solid state microwave oscillator [Gun63].

|

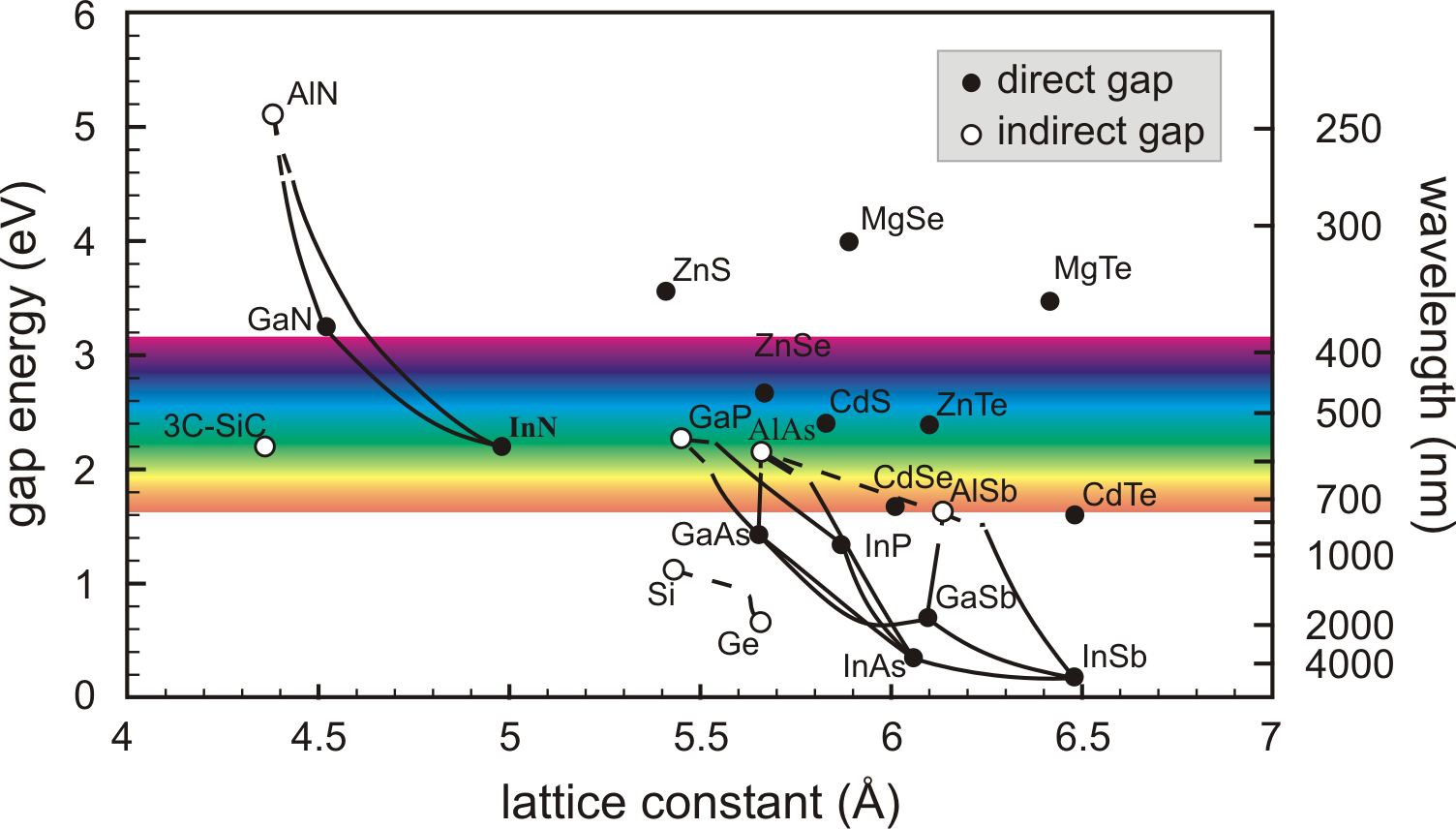

Figure 3.1 shows the energy gaps and the

lattice constants of of the most important elemental and binary

cubic semiconductors. The connecting lines consider the case of

ternary compounds, composed of various ratios of the corresponding

binary materials. The compound

![]() maintains nearly

the same lattice constant with the change of the Al mole fraction.

This property and the related high quality heteroepitaxy have

opened new possibilities for advanced devices like double

heterostructure lasers, high electron mobility transistors and

heterostructure bipolar transistors; to describe the large

possibilities offered by the epitaxial growth using

maintains nearly

the same lattice constant with the change of the Al mole fraction.

This property and the related high quality heteroepitaxy have

opened new possibilities for advanced devices like double

heterostructure lasers, high electron mobility transistors and

heterostructure bipolar transistors; to describe the large

possibilities offered by the epitaxial growth using

![]() , and in general III/V compounds, a new expression

has been coined: bandgap engineering.

, and in general III/V compounds, a new expression

has been coined: bandgap engineering.

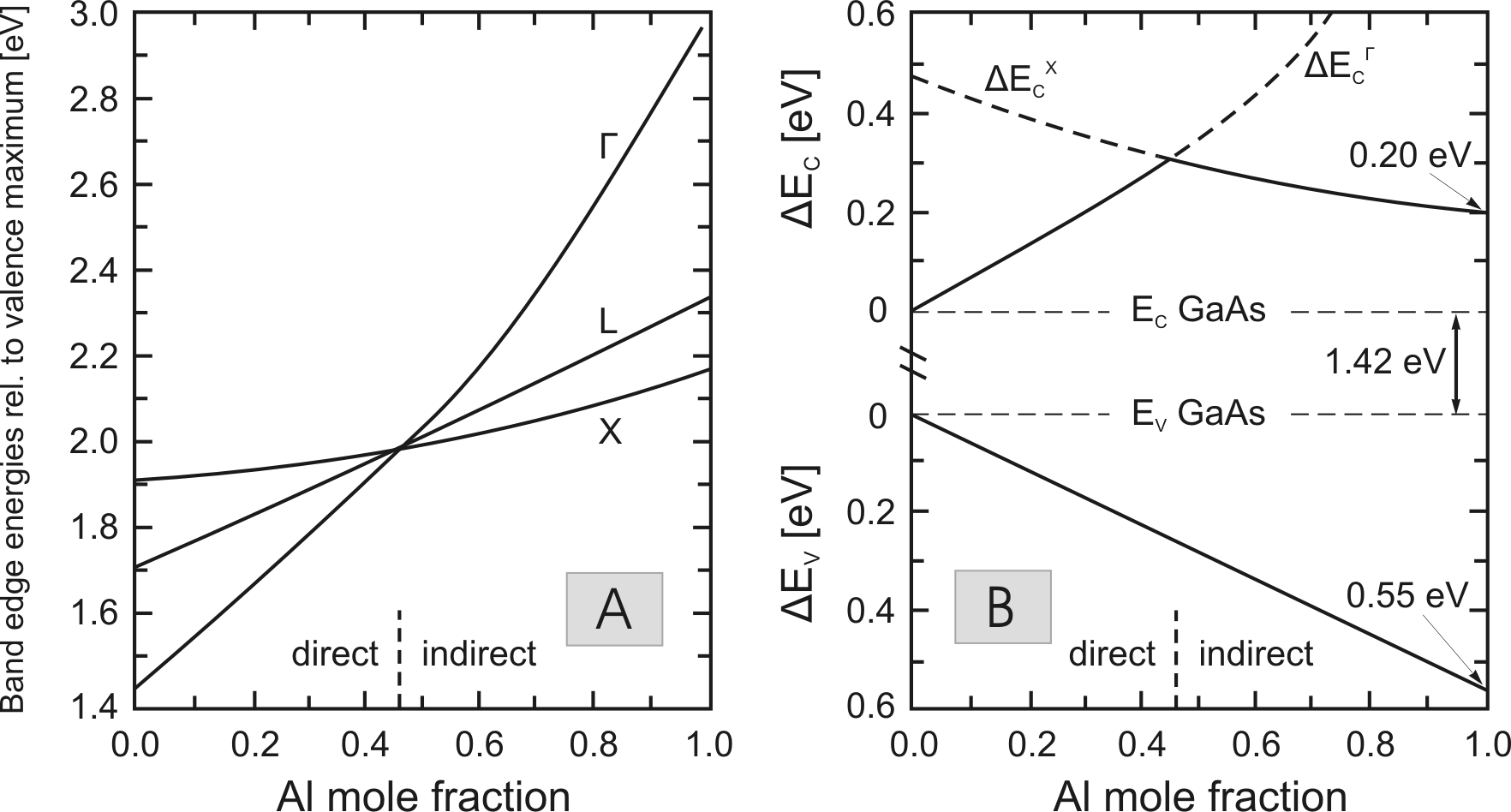

In Fig. 3.2, the bandgap energy of the

![]() material system is plotted versus the Al

concentration in different points of the Brillouin zone. At about

45% Al, the transition between direct and indirect bandgap can be

observed.

material system is plotted versus the Al

concentration in different points of the Brillouin zone. At about

45% Al, the transition between direct and indirect bandgap can be

observed.

|

As in the case of arsenides, between group III - elements and

nitrogen, the nature of the bond is mainly covalent. However, for

the nitrides, the large difference in the electronegativities

causes a strong ionic component, which means very high bonding

energies (AlN 11.5, GaN 8.9 and InN

![]() ) and

consequently excellent thermal and chemical stability. In contrast

to GaAs, the thermodynamically stable phase of these materials is

the hexagonal wurtzite structure,

) and

consequently excellent thermal and chemical stability. In contrast

to GaAs, the thermodynamically stable phase of these materials is

the hexagonal wurtzite structure,

![]() . Beside to

. Beside to

![]() , a metastable

, a metastable

![]() with zincblende

structure exists if very thin layers of GaN and InN are grown on

cubic substrates like GaAs or silicon. The nitride materials with

wurtzite structure form an alloy system (InGaN, AlGaN, InAlN),

whose direct bandgaps range from 0.7 to

with zincblende

structure exists if very thin layers of GaN and InN are grown on

cubic substrates like GaAs or silicon. The nitride materials with

wurtzite structure form an alloy system (InGaN, AlGaN, InAlN),

whose direct bandgaps range from 0.7 to

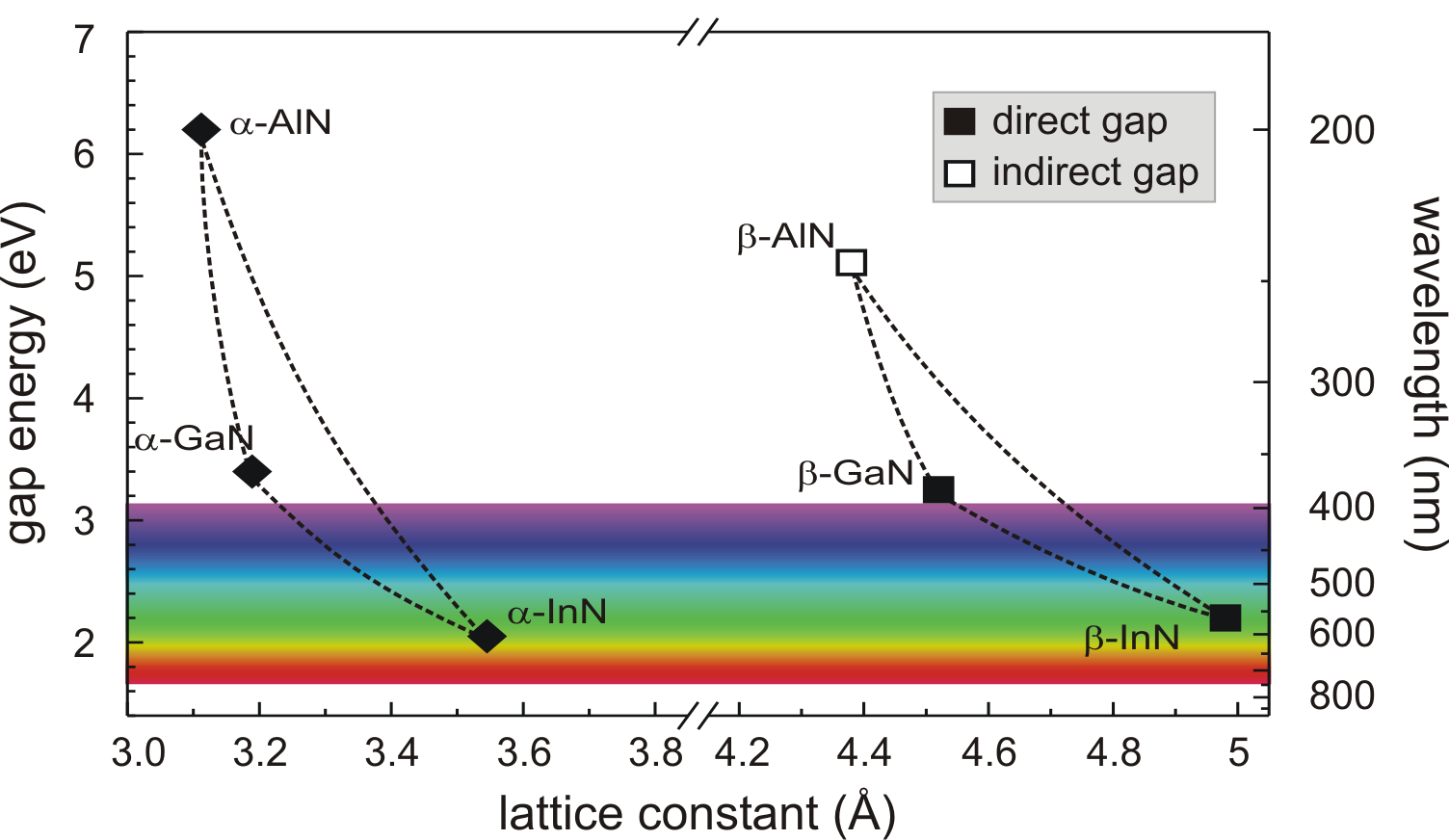

![]() (Fig. 3.3). These give to group III-nitride

unique optical properties, making them suitable for a large

spectrum of optoelectronic applications. Another peculiarity of

group III nitrides, in comparison with arsenides, is the existence

of strong spontaneous and piezoelectric polarization fields. This

property leads to an additional carrier accumulation at the

strained interfaces

(Fig. 3.3). These give to group III-nitride

unique optical properties, making them suitable for a large

spectrum of optoelectronic applications. Another peculiarity of

group III nitrides, in comparison with arsenides, is the existence

of strong spontaneous and piezoelectric polarization fields. This

property leads to an additional carrier accumulation at the

strained interfaces

![]() in 2DEG structures,

enhancing the electron concentrations in GaN HEMTs.

in 2DEG structures,

enhancing the electron concentrations in GaN HEMTs.

The GaAs Gunn diode structures considered in this thesis have been

grown by molecular-beam epitaxy (MBE) on 2-inch semi-insulating

GaAs substrates in a Varian ModGen II MBE system. The principle

scheme of the MBE growth chamber is shown in

Fig. 3.4. The substrate holder can be heated up

to 900

![]()

![]() C . The source materials Ga, As, In, Al, Si (for

n-doping) and Be (for p-doping) are placed in the effusion cells.

The growth rate can be measured by a RHEED3.2 system and is

controlled by tuning the cells temperature. In order to monitor

the doping levels, calibration samples are periodically grown and

characterized by Hall and CV measurements (sections

4.3 and 4.4).

C . The source materials Ga, As, In, Al, Si (for

n-doping) and Be (for p-doping) are placed in the effusion cells.

The growth rate can be measured by a RHEED3.2 system and is

controlled by tuning the cells temperature. In order to monitor

the doping levels, calibration samples are periodically grown and

characterized by Hall and CV measurements (sections

4.3 and 4.4).

A typical layer sequence of a GaAs Gunn diode with a graded gap

injector is sketched in Fig. 3.5.

It consists mainly of an undoped AlGaAs graded barrier structure

followed by a ![]() doping and a thick low doped GaAs active

region. The grading is linear, starting from 1.7% up to the

maximum Al value. The role of the two

doping and a thick low doped GaAs active

region. The grading is linear, starting from 1.7% up to the

maximum Al value. The role of the two

![]() GaAs

spacers is to avoid doping diffusion in the graded barrier.

GaAs

spacers is to avoid doping diffusion in the graded barrier.

In this work, different structures have been considered:

The first structure (W16016) is mainly used as a reference. Even if the electrical measurements show no hint of a hot electron injector, W16016 allows a comparison with the other structures. Wafers W18006 and W18021, which have the same full-working graded gap injector, were grown to demonstrate the influence of the active region length on the diode high frequency behaviour. Finally, in wafers from W18038 to W18041, the role of the maximum Al content in the injector has been examined.

|

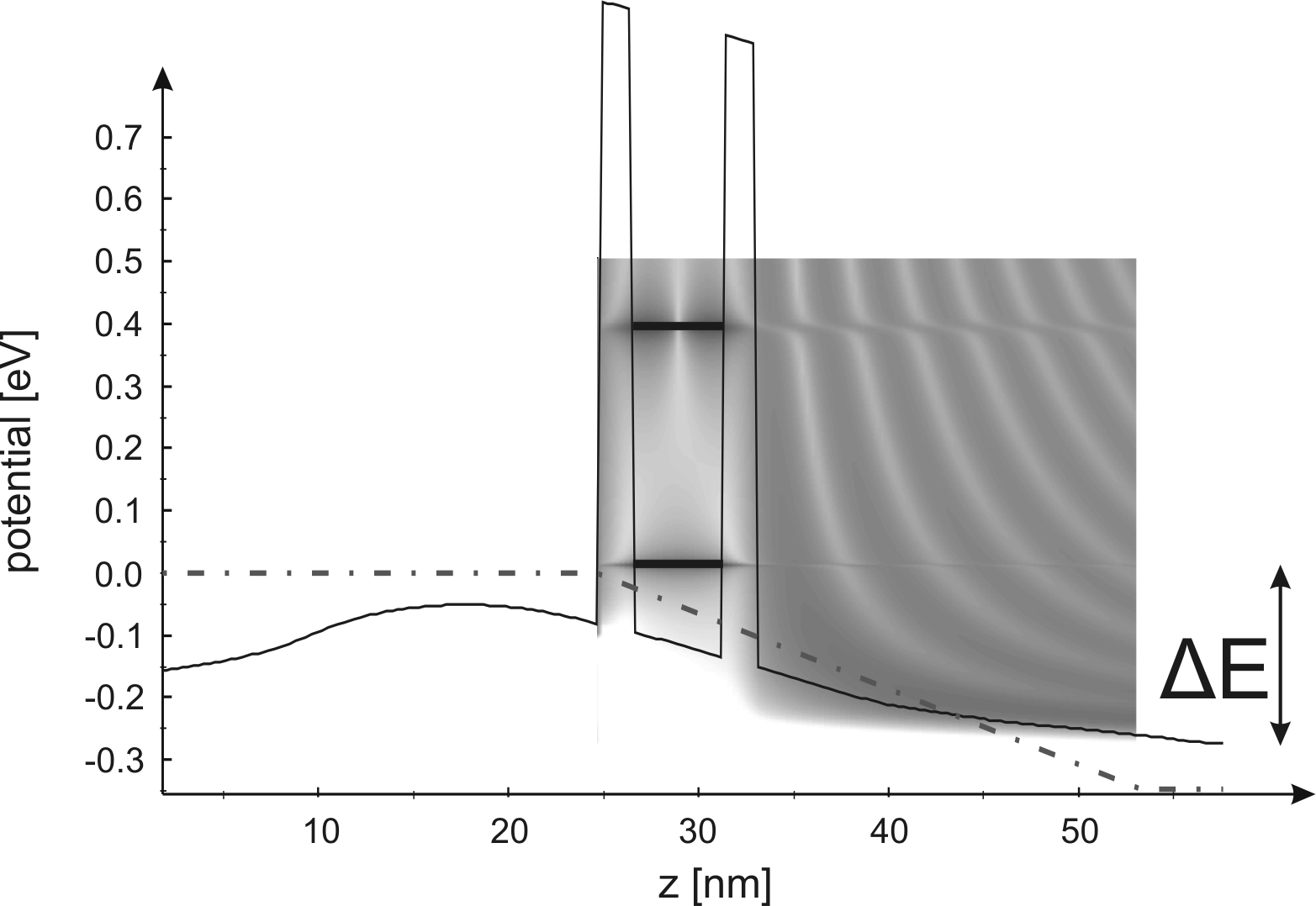

The simulation of the resonant tunneling injector was done with

the software package Wingreen [IM]. This is based on a

self-consistent real-time Green's function approach [Ind99].

A simulation example is shown in Fig. 3.6. The

conduction band and the local density of states of a RTI are

presented for an applied bias voltage. The chosen bias voltage

corresponds to a current density in the range 23-27 ![]() . The

layer structure has to be so that the following condition is

satisfied: the first transmission energy level for the given

current density range has to match the energy difference between

the L- and the

. The

layer structure has to be so that the following condition is

satisfied: the first transmission energy level for the given

current density range has to match the energy difference between

the L- and the ![]() -valley (

-valley (

![]() for GaAs). In order to make the

RTI competitive, a further specification has been defined: the

voltage drop on the RTI for the working current conditions, must

be much lower than the one on the GGI.

for GaAs). In order to make the

RTI competitive, a further specification has been defined: the

voltage drop on the RTI for the working current conditions, must

be much lower than the one on the GGI.

In Fig. 3.7, a typical layer sequence of

the RTI GaAs Gunn diode is presented. The structure is very

similar to that of GGI GaAs Gunn diode: the active region, the

spacers and the ![]() -doping layers have not been changed. The

injector itself is undoped and consists in a sequence of

AlAs/GaAs/AsAs (

-doping layers have not been changed. The

injector itself is undoped and consists in a sequence of

AlAs/GaAs/AsAs (

![]() /

/

![]() /

/

![]() , W18069). A second wafer

has been grown decreasing the AlAs thickness from 6 to

, W18069). A second wafer

has been grown decreasing the AlAs thickness from 6 to

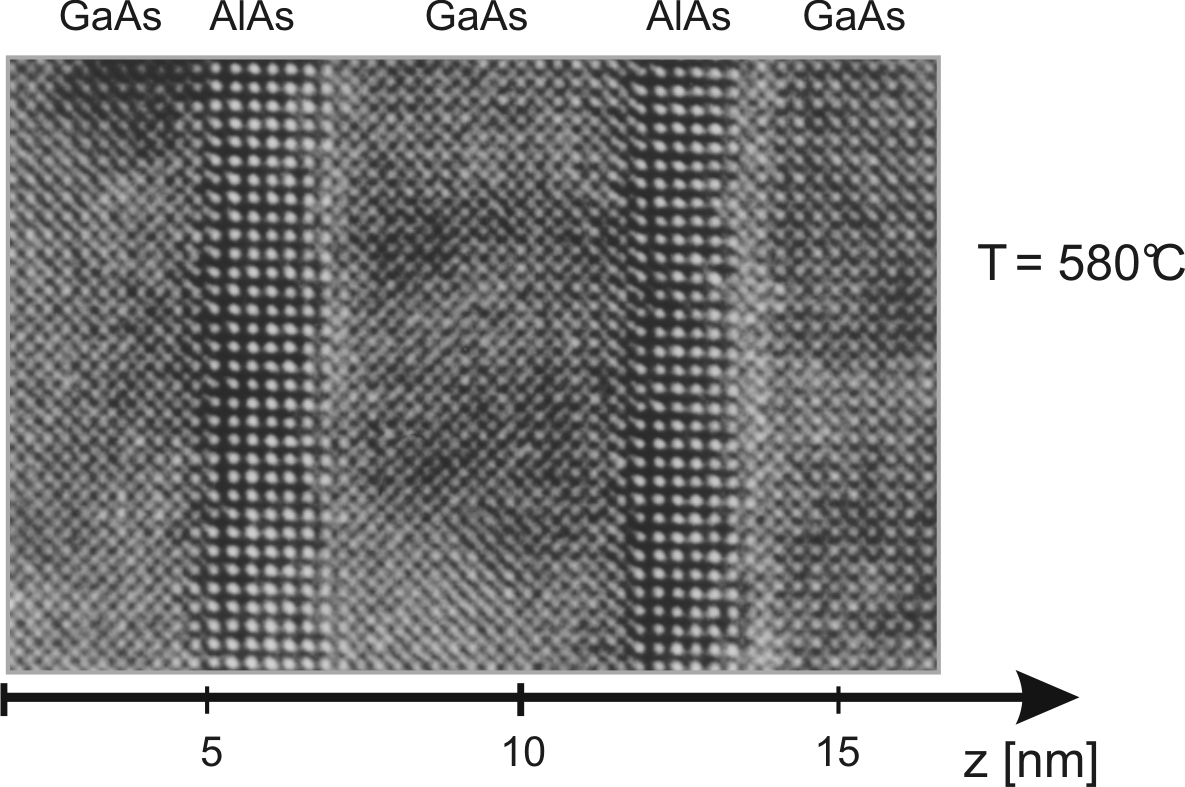

![]() (W18069). The High Resolution Transmission

Electron Microscopy (HRTEM) image illustrates a resonant tunneling

double barrier with

(W18069). The High Resolution Transmission

Electron Microscopy (HRTEM) image illustrates a resonant tunneling

double barrier with

![]() of AlAs. The sample has

been grown at

of AlAs. The sample has

been grown at

![]() C, an optimal temperature

for well defined GaAs/AlAs interfaces [Lan99].

C, an optimal temperature

for well defined GaAs/AlAs interfaces [Lan99].

|

The MOVPE is characterized by large-area growth capability, high

surface mobility of the precursor gaseous molecules, good layer

uniformity and precise control of the epitaxial deposition. These

reasons together with the higher growth rate, made the MOVPE to be

the favourite growth method for industrial purposes. By this

technique, the gas phase growth precursors are transported by a

carrier gas to a heated substrate, where the precursors are

pyrolysed and the nitride film is deposited. The diffusion of the

active materials to the substrate are favored by the depletion at

the surface and the consequent concentration gradient of these

materials in the gas phase, due to their consumption during the

growth. The obtained byproducts are then transported out from the

reactor together with the unused reactants. As group III sources,

trimethylgallium or triethylgallium (-indium,-alluminium) are

used, whereas the common nitrogen source is ammonia (![]() ). The

high thermal stability of

). The

high thermal stability of ![]() , although still low compared to

, although still low compared to

![]() , is one reason to use high substrate temperatures,

typically more than 550

, is one reason to use high substrate temperatures,

typically more than 550![]() C for InN and above 900

C for InN and above 900![]() C

for GaN and AlN. The high growth temperature and thus the high

nitrogen vapor pressure lead to the problem of nitrogen loss from

the nitride film and to carbon contamination from the

decomposition of the organic radical during metalorganic

pyrolysis. The loss of nitrogen is usually alleviated by the use

of high V/III gas ratios during the deposition. The extreme

requirements for the nitride growth have led also to the

development of new MOVPE reactor designs.

C

for GaN and AlN. The high growth temperature and thus the high

nitrogen vapor pressure lead to the problem of nitrogen loss from

the nitride film and to carbon contamination from the

decomposition of the organic radical during metalorganic

pyrolysis. The loss of nitrogen is usually alleviated by the use

of high V/III gas ratios during the deposition. The extreme

requirements for the nitride growth have led also to the

development of new MOVPE reactor designs.

The GaN Gunn diode structures, considered in this thesis, have

been grown by MOVPE in an Aixtron AIX200 reactor on two inch ![]() substrates. Unlike the MBE system, RHEED is not suitable for

in-situ monitoring of the growth rate in the high-pressure

environment like MOVPE. RHEED requires a high electron mean free

path, which can be achieved only in ultra high vacuum conditions.

The growth rate is therefore determined by normalized

reflectometry. A more accurate description of the MOVPE epitaxy

and the experimental setup can be found in [Kal03].

substrates. Unlike the MBE system, RHEED is not suitable for

in-situ monitoring of the growth rate in the high-pressure

environment like MOVPE. RHEED requires a high electron mean free

path, which can be achieved only in ultra high vacuum conditions.

The growth rate is therefore determined by normalized

reflectometry. A more accurate description of the MOVPE epitaxy

and the experimental setup can be found in [Kal03].

simone.montanari(at)tiscali.it 2005-08-02